hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Interview] Blueprint for “de-risking” came from Scholz’s “smart diversification,” says German lawmaker

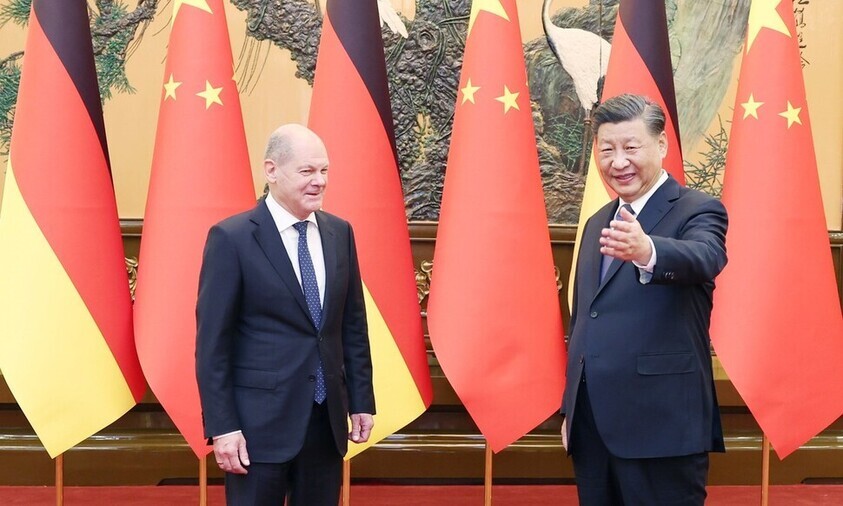

The first Western leader to pay a visit to Beijing after President Xi Jinping was all but ensured a third consecutive term last October was Chancellor Olaf Scholz of Germany. In a meeting between the two heads of state that took place on Nov. 4, Scholz underscored that Germany doesn’t want to decouple from China, and would pursue “smart diversification” instead.

Around five months later, in late March of this year, Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, formally announced Europe’s new strategy for China: “de-risking.” Scholz’s strategy of diversification was renamed to one of de-risking, a position which has cemented itself as the strategy for China of choice in the West, including the EU, the US, and Japan.

Speaking to the Hankyoreh on June 28, Nils Schmid, 50, a member of the German Bundestag, said that Scholz was the first in the world to use the notion of diversification when it came to strategies for dealing with China, emphasizing that Germany was the originator of the de-risking strategy formally adopted by the EU and the Group of Seven.

Like Scholz, Schmid is a member of the Social Democratic Party. He was first elected to the federal parliament in 2017, and has served as his party’s spokesperson for foreign policy since 2018.

Germany released its first-ever national security strategy on June 14, followed by its “Strategy on China” on July 13.

Nils Schmid: The document itself states that the aspect of systemic rivalry has become predominant in our relationship with China, because China is eager to show to its own citizenry, and also to the world, that its system of governance is superior. The West, in the eyes of the Chinese, is in decline, and democracy and the rule of law as we define it in the West are inferior and awkward when it comes to realizing broad goals of social welfare and justice, and economic development. We are convinced that democratic governance will prevail in the long term and can secure equality, sustainable progress, and social cohesion. We are confident enough to take on this challenge and to show first of all, to our own citizens, but also to other parts of the world, that democracy works fine. And it works fine not only in Europe or North America, but also in Asia as Korea shows, and Japan shows, and Taiwan shows.

On the other hand, there are well-established and well-known cases of economic and technological competition going on with China. And of course, there is room and there should be room for partnership when it comes to pursuing global common goods like global health and the protection of our climate.

So we consider these three dimensions to be relevant to our relationship with China. But we also have to admit that systemic rivalry has become more and more prominent.

Hankyoreh: China is Germany’s biggest trading partner. What does the Chinese market mean for Germany?Schmid: There is a misperception not only in Germany, but also in many other parts of the world, but our biggest trading partner is the European Union. Since this single market consists of 26 nations, it seems that China is the biggest trading partner. But this is misleading because we have to take the EU nations together, as trade with these nations is governed by the same rules of the European single market.

China is a huge market, and will continue to be a huge market and probably a growing market. There are lots of business opportunities out there as well, although the long-term demographics are not so promising. But still, when it comes to raising revenues or rising income levels, we can be confident that for the foreseeable future that the Chinese market will remain an important market for German and European companies. And they have every latitude to continue doing business there. They should simply be aware of the risks when it comes to lopsided dependencies and heavy dependencies for certain raw materials or on certain supply chains.

Hankyoreh: The EU has stressed it’s not decoupling with China, but “de-risking.” At the same time, Chancellor Olaf Scholz has used the term “diversifying.” What’s the difference?

Schmid: It has become clear over the last few months that the common thread of EU policy towards China is de-risking, and it was the chancellor who used the word for the first time. Before his visit to Beijing [in November 2022], he published an op-ed in a very important newspaper, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, in which he spelled out his ideas about China policy. It’s de-risking. Decoupling is off the table. It was never a realistic option. [Politico also ran a guest essay from Scholz on Nov. 3, 2022, titled “We don’t want to decouple from China, but can’t be overreliant,” in which he calls for “smart diversification.” -eds]

De-risking means that we look at certain risks associated with dependencies on China when it comes to raw materials. Diversification is the flip side of the coin, meaning that if you want to de-risk, you need diversification. It’s very obvious to me and to many decision-makers in the German business community that the diversification strategy, followed by many Korean and Japanese companies in Asia, for example, by entering markets in Southeast Asia, like Vietnam, but also aiming at the huge Indian market, is very promising. Unfortunately, too many German companies chose the easy path for too long, meaning they bet on continuing growth in China.

Hankyoreh: President Macron of France appears to be trying to find a middle ground between the US and China. Does Germany intend to do the same?

Schmid: There can be no middle ground or equidistance between China and the US for Europeans. When it comes to basic values to our basic understanding of how society, government and the economy works, we are on the same page with the US and we defend the values-based multilateral order. In many aspects also of interest to the US, there might be diverging interests, because European economies depend to a large extent on foreign trade. When it comes to purely business-related issues, there is a healthy degree of competition going on between the US and Europe.

Hankyoreh: Germany’s strategy on China came out later than anticipated. Was this the result of internal disagreements?

Schmid: Well, that’s how politics works in any country. Of course, there was some interagency debate, which is quite usual. In the end, what really made the definite adoption of this strategy so complicated was issues of secondary or third order: budget issues, the system of division of labor between the state level and the federal level, and more. It took far too long to be resolved despite the substance of the text already having been written by March or so.

Hankyoreh: How do you assess the mutiny by the Wagner Group?

Schmid: Well, first of all, it’s part of a power struggle inside Russia. What [Yevgeny] Prigozhin managed to do is exhibit the falseness of Putin’s propaganda on the war in Ukraine. It was an attack on the basis of Putin’s government, which is nepotism and corruption. That is, this was not so much a military attack, but a political attack on the very foundation of Putin’s hold on power. Prigozhin has now been sidelined and more or less ousted from Russian domestic politics. But the fact that this could happen showed Putin’s weakness and vulnerability.

Hankyoreh: Do you expect any more volatility within Russia?

Schmid: We don’t expect Putin or his system to lose power very soon. And even if Putin quits or exits for any reason, the power structure he has established in Russia over the last 20 years will most probably continue to hold. We should not expect anybody succeeding Putin to be any more pliable on foreign policy or even to be more democratic than Putin. I would say we are in a protracted conflict with Russia and Russia’s aggressive foreign policy is there to stay for some time.

Hankyoreh: Do you think Sino-Russian relations will remain strong?

Schmid: The Prigozhin incident is a blow to Putin not only domestically but also abroad. For the first time, his reputation as a strong leader has been put into doubt. Putin is not as strong as he wants to be seen. I think the Chinese leadership has already factored that in. This is not a real alliance. This is a cooperation between two revisionist countries who want to corner the West, and who want to increase their influence to the detriment of the US. This is what binds them together.

By Noh Ji-won, Berlin correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor [Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0703/8717199957128458.jpg) [Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor

[Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor![[Column] How opposing war became a far-right policy [Column] How opposing war became a far-right policy](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0702/5017199091002075.jpg) [Column] How opposing war became a far-right policy

[Column] How opposing war became a far-right policy- [Editorial] Korea needs to adjust diplomatic course in preparation for a Trump comeback

- [Editorial] Silence won’t save Yoon

- [Column] The miscalculations that started the Korean War mustn’t be repeated

- [Correspondent’s column] China-Europe relations tested once more by EV war

- [Correspondent’s column] Who really created the new ‘axis of evil’?

- [Editorial] Exploiting foreign domestic workers won’t solve Korea’s birth rate problem

- [Column] Kim and Putin’s new world order

- [Editorial] Workplace hazards can be prevented — why weren’t they this time?

Most viewed articles

- 1South Koreans living near border with North unnerved by return of artillery thunder

- 2Car behind deadly crash began rapid acceleration after exiting underground garage

- 3S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 4Democrats ride wave of 1M signature petition for Yoon to be impeached

- 510 days of torture: Korean mental patient’s restraints only removed after death

- 6Hyundai Motor sets up one-stop shop for EV production in Indonesia

- 7[Editorial] Korea needs to adjust diplomatic course in preparation for a Trump comeback

- 8[Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor

- 9Families, friends mourn loved ones cut down in prime in deadly car crash

- 10Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions