hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Can S. Korea qualitatively change its alliance with the US?

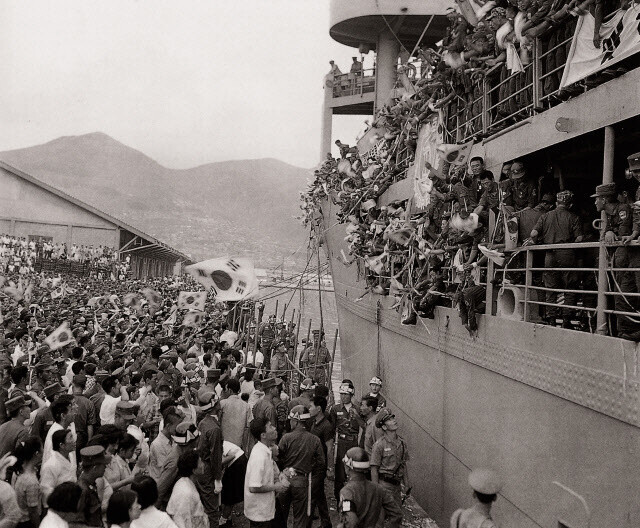

“WELCOME! MUTUAL DEFENSE TREATY BETWEEN ROK & USA”

Thirteen days after the Korean War came to a stop, the top story on the front page of the Chosun Ilbo newspaper on Aug. 9, 1953, was about a ceremony for the initialing of the mutual defense pact between the two countries.

The day before, then-South Korean Foreign Minister Pyon Yong-tae and US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles had met at the Blue House. Thirty seconds later, the treaty was provisionally signed.

Unusually, the title of the newspaper’s story was printed in English — a sign of the giddy mood in South Korea at the time over the treaty’s provisional signing. Around two months later, on Oct. 4, the treaty was officially signed in Washington, marking the beginning of a South Korea-US alliance that has lasted for 70 years since.

The initialing ceremony was attended by all the members of the South Korean Cabinet and then-President Syngman Rhee. The subtitle of another article in the Dong-A Ilbo newspaper — reading “Ample military support in the event of a renewed enemy invasion” — shows how the regime at the time saw the treaty as providing a robust security guarantee.

But the content was not just a reflection of South Korea’s demands. A joint statement issued by Rhee and Dulles concurrently with the initialing shows signs of tensions and cracks between the two sides.

The US government made it clear that the South Korean military would be under the command of the UN Command, which meant US Forces Korea. The joint statement stressed that South Korea would not engage in any “unilateral action” under the UN Command.

This read as a message curbing any unilateral actions on the part of Rhee, who was calling at the time for advancing on the North to achieve unification. The US also included a safeguard stating that if war did break out again on the peninsula, it would only participate with the approval of its Congress. In effect, it was spurning Rhee’s demands for automatic intervention in such a scenario.

This was Article III of the treaty, which opposes “an armed attack in the Pacific area” and states that each party “declares that it would act to meet the common danger in accordance with its constitutional processes.”

This is the context behind assessments such as that of University of North Korean Studies professor Koo Kab-woo, who described the treaty as having been “created in a form where the US passively accedes to South Korea’s demands.” In effect, the US opted for an alliance treaty as a safety valve for maintaining the current order — a divided Korean Peninsula — by reining in the Rhee regime’s calls for an advancement on North Korea to achieve reunification.

In this manner, the alliance between South Korea and the US was born amid shared circumstances and diverging objectives.

That brings us to the present, 70 years later. The alliance between Seoul and Washington is often lauded as a “successful” one. During the Cold War, South Korea fulfilled its purpose for the US as a “forward base in the struggle against communism” and the “showcase of capitalism and democracy.” Leaning on the US for its national security, Korea was able to make its great leap into advanced nation status. It became the only country in the world to have transitioned from a beneficiary of aid to a provider of aid in the postwar era.

The seven-decade alliance between South Korea and the US has had its share of ups and downs.

Park Myung-lim, a professor at Yonsei University, has characterized Korea’s alliance with the US as one “with substantial tension” and “conflictual.” Using his concept of the “American boundary,” Park estimates, “The US adhered to a policy that negated the establishment of either a leftist communist regime or right-wing fascist one” in Korea. This was how the scholar referred to the Janus-faced nature of the US in Korea during the Cold War as both a guarantor of authoritarianism and a sponsor of democracy.

Washington did not support the April 19 revolution in 1960. It was aware of, but did nothing to stop, the military coup by Park Chung-hee on May 16, 1961, and in the immediate aftermath, spurned Prime Minister Chang Myon’s request to quash the mutiny. When Chun Doo-hwan staged his own coup on Dec. 12, 1979, and oversaw a massacre in Gwangju the following May, the US stayed silent and abetted Chun.

For these reasons and more, many Koreans who lived through the military dictatorships of the 1960s-80s remember the US as a backer of dictatorship. They also form the historical backdrop for the anti-American sentiment that was rampant in Korea in the 1980s through the 2000s.

Silence and connivance are fruits of America’s hegemonic strategy. In the early 1960s, the Kennedy administration’s assessment of the situation in the newly formed and small powers of the Third World was that there were three possibilities: a decent democratic regime, a continuation of military dictatorship, or a socialist regime. “We ought to aim at the first,” he said, “but we really can’t renounce the second until we are sure that we can avoid the third.” Korea was no exception.

At the same time, the US sponsored “Sasanggye” — “The Realm of Thought” — the monthly magazine that served as the intellectual center for South Korean democracy in the 1950s and 1960s.

The US Information Service (American cultural service) helped the magazine find its footing by offering to provide the publication with six months’ worth of paper to use for publication.

Those working at “Sasanggye” were also given exclusive distribution of major US magazines like “Time” and “Life.” The US and Sasanggye Group were collaborators in the mission of helping American liberalism (democracy) take root in South Korea.

After the heated rise of anti-US sentiment in South Korea following the massacre in Gwangju in May 1980, the US was kept busy during the struggle for democracy in June of 1987, as it tried to keep tabs on both the military dictatorship and the democratic revolution by the people.

This was the last time that the US acted as a “sponsor for democracy” in South Korea.

The alliance between the two countries consolidated its position in the years that followed, leaning on the emerging North Korean nuclear crisis during the changes brought on the South’s uprising for democracy in 1987 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

The alliance expanded into the economic sphere. The two pillars bolstering the alliance in the 21st century are the mutual defense treaty and the free trade agreement (FTA) between Seoul and Washington. The FTA was negotiated and signed during the Roh Moo-hyun administration (June 2007) and entered into force during the Lee Myung-bak administration (March 15, 2012).

With the rise of South Korea, the alliance between South Korea and the US has evolved from that akin to a “guardianship” to something closer to a “partnership.”

South Korea’s long-term deployment of its Zaytun Division to Iraq to help with reconstruction symbolizes this shift in the alliance.

While South Korea’s deployment to Vietnam (1964-1973, 48,000 troops) was characterized as a “mercenary” mission with the US paying for all the costs, South Korea paid for the local presence and activities of its troops in Erbil, which were the largest and longest deployment of South Korean troops since Vietnam (19,000 troops deployed from February 2004-December 2008).

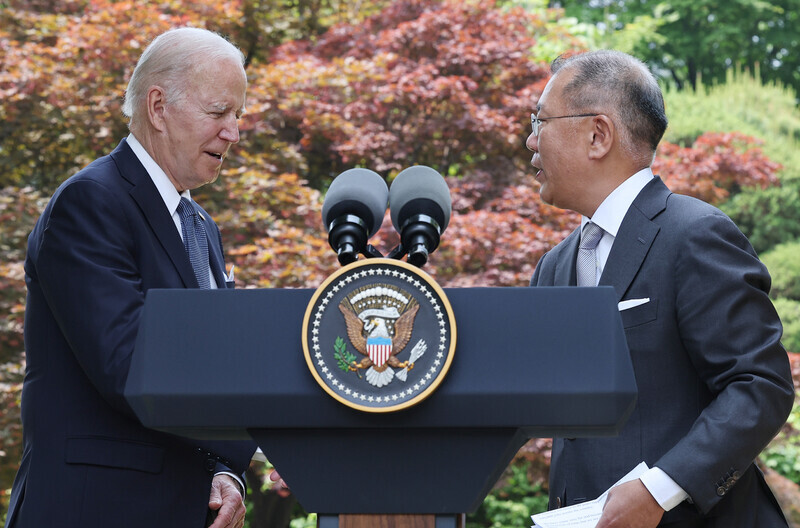

In recent years, the US has increasingly pressured or made requests of its ally according to its own national interests or international strategy. US President Joe Biden’s visit to South Korea in May 2022, shortly after the inauguration of the Yoon Suk-yeol government is illustrative of the shift in relations between the two countries.

Upon arriving at Osan Air Base on May 20, Biden went straight to the Samsung Electronics’ Pyeongtaek campus, where he called for strengthening the Korea-US alliance through semiconductors.

Two days later, before leaving Seoul on May 22, Biden met privately with Hyundai Motor Group Chair Chung Eui-sun at the Hyatt, where he was staying, and secured an announcement of US$5 billion in additional investment in the US by 2025.

His visit schedule started with Lee Jae-yong of Samsung and finished with Chung from Hyundai/Kia. This signified that the economy was his main priority — and that even there, it was less about how he could help and more about what he could get.

The “America First” mentality has been damaging to US’ image as an ally.

Citing the need for global supply chain reorganization, Biden has been overtly pushing Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix to cut off ties with China and not to fill the gap left there by US semiconductor companies. He also declined to include Hyundai/Kia among the targets for electric vehicle tax credits in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

This stands in contrast with the scene of him patting Chung Eui-sun on the back assuring him that the US would “not let you down.” The alliance has been made a secondary consideration to an American economic recovery.

The shifting in the South Korea-US alliance can also be seen in Washington’s strategy to pressure Beijing. The US has looked for stronger trilateral security cooperation with South Korea and Japan as a way of hemming China in, and it has demanded improved relations between Seoul and Tokyo as a necessary step in that direction.

After Yoon came out unilaterally with a solution of third-party compensation to victims of forced labor mobilization during the Japanese occupation, Biden told him at their bilateral summit in Washington last April that he wanted to thank him for his “political courage and personal commitment to diplomacy with Japan.”

The increasing decoupling of the two sides’ national interests raises the need for a new concept of our relationship.

An overwhelming majority of South Koreans still name the US as our most important neighbor when it comes to peace on the Korean Peninsula. In a Gallup Korea opinion survey during the second week of August 2022, 75% of respondents selected the US as Korea’s most important neighbor, compared with just 13% who picked China.

Yet South Koreans are not entirely on board with policies that uniformly favor the US. When asked for their opinion on South Korea’s best diplomatic response to the US-China competition in a National Barometer Survey between July 11 and 13, 2022, an equal 38% of respondents each chose “foreign policies based on the South Korea-US alliance” and “balanced US and China policies that take China into account.”

Similarly, focus group interviews with different generations conducted by the Hankyoreh last May and June with the opinion research organization Human n Data found many participants viewing a more balanced diplomatic approach as necessary.

“Sustaining the South Korea-US alliance, denuclearizing the Korean Peninsula, and establishing a peace regime on the peninsula is an impossible trinity of policy goals that cannot be achieved simultaneously,” explained University of North Korean Studies professor Koo Kab-woo.

“South Korea is facing a trilemma,” he concluded.

This is an answer to the question of why the Korean Peninsula failed to achieve peace despite three inter-Korean summits and two North Korea-US summits in 2018 and 2019 — and it also shows the two conflicting faces of the South Korea-US alliance as both a safety valve for and obstacle to peace on the peninsula.

As 2023 marks the 70th anniversary of both the alliance and the armistice, South Korea has reached a point as a society where it needs to confront the “paradox of success” directly, examining not only the good that has come from the alliance but also its darker aspects.

On the topic of the “future of the South Korea-US alliance,” Moon Chung-in — someone who formerly served as Sejong Foundation chairperson and who has long been involved in friendly cooperation between South Korea and the US — raised three main questions

“Is the alliance a means or an end in itself?” he asked. “Can the national interests of South Korea be unified with those of the US? And can strategic dependence on the US coexist with South Korean autonomy?”

An alliance presupposes an enemy. Can South Korea achieve a qualitative change in the alliance for the sake of denuclearization, peace, and prosperity on the Korean Peninsula? Is the idea of a collaborative relationship with the US that does not involve an alliance just an impossible dream?

When you can’t imagine something, it can never become reality.

By Lee Je-hun, senior staff writer

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing? [Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0705/2917201664129137.jpg) [Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?

[Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?![[Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor [Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0703/8717199957128458.jpg) [Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor

[Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor- [Column] How opposing war became a far-right policy

- [Editorial] Korea needs to adjust diplomatic course in preparation for a Trump comeback

- [Editorial] Silence won’t save Yoon

- [Column] The miscalculations that started the Korean War mustn’t be repeated

- [Correspondent’s column] China-Europe relations tested once more by EV war

- [Correspondent’s column] Who really created the new ‘axis of evil’?

- [Editorial] Exploiting foreign domestic workers won’t solve Korea’s birth rate problem

- [Column] Kim and Putin’s new world order

Most viewed articles

- 110 days of torture: Korean mental patient’s restraints only removed after death

- 2What will a super-weak yen mean for the Korean economy?

- 3Real-life heroes of “A Taxi Driver” pass away without having reunited

- 4Koreans are getting taller, but half of Korean men are now considered obese

- 5Ahead of 2018 Olympics, hanok village opens in Gangneung

- 6Members of North Korea’s cheerleading squad reflect on their Olympic experience

- 7Former bodyguard’s dark tale of marriage to Samsung royalty

- 8[Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?

- 9Democrats ride wave of 1M signature petition for Yoon to be impeached

- 10Japan’s lack of transparency on Fukushima water is sparking fear in neighbors, says Japanese expert