1. Bullet after payslip

Youngone workers leave the Korea Export Processing Zone(KEPZ) in Chittagong, Bangladesh. The Korean company is known as manufacturer of the outdoor brand Northface. It first invested in Bangladesh in 1980. In 1999, it bought 500ha of land for US$14 million from the Bangladeshi government, and established the first private export processing zone in the country. Now Youngone operates 17 corporate bodies that produce garments and shoes. It also owns an airline in Bangladesh. Youngone, employing 68,000 workers, is the biggest foreign investor in Bangladesh, and is one of the biggest manufacturers of outdoor wear in the world. (by Ryu Yi-geun, staff reporter)

There is an old saying that Bengal, along with Punjab, feeds all of India. With abundant water from the Ganges and a warm climate throughout the year, they can have as many as three rice harvests a year in Bangladesh, which means ‘the country of Bengal’.

Only Youngone factories are operating inside KEPZ currently. On a gate of KEPZ is a sign saying child labor is prohibited in English and Bengali. Child labor is a long standing issue in developing countries including Bangladesh. (by Ryu Yi-geun, staff reporter)

Parvin Akter worked in this shoe factory owned by Youngone. Most of the workers are female. Youngone‘s biggest buyer is VF which owns the outdoor brand Northface. Youngone manufactures about 40% of Northface products sold worldwide. Nike, Puma, Engelbert-Strauss, Ralph Lauren are also major buyers of Youngone. (by Ryu Yi-geun, staff reporter)

Nashima still works in the factory where her sister was killed. Her colleagues said she cried in front of her sewing machine for days after her sister’s death. Nashima said “It‘s scary to work in this place, but I have a bad stomach that demands food.” Now she is the only earner in the family. (by Ryu Yi-geun, staff reporter)

But not everybody enjoys the affluence. Just like any other lower-class people, Parvin Akter’s father owned no land. He worked in other people’s farms or pulled rickshaw all his life.

He died in 2012, leaving a sick wife and four daughters. That’s when a foreign company called ‘Youngone’ built a huge factory not far from Parvin’s home. After hearing that the factory was recruiting workers, Nashima, Parvin’s younger sister, got a job. Soon she started working as a sewing machine operator. The training she had received from a sewing school in downtown Chittagong paid off. Nashima brought home around 6,000 taka (US$77) a month.

Thanks to Nashima, the family could eat three meals a day. But that wasn’t enough. They couldn’t afford to take the sick mother to a doctor, or even a pharmacy. The family had not been able to pay off its 3,000 taka of debt (US$38). Parvin, who had been handling household chores joined the factory last September. With Nashima’s recommendation, she got hired without much trouble. That’s how people usually get jobs in this country-by recommendation from family members or friends.

Parvin is 21 years old. Bangladeshi women around this age usually get married, but Parvin didn’t want to. She’d rather be with her mother. She used to tell her mother, “I won’t get married. I will make money and live with you.”

Parvin was optimistic about the future. She was sure she would be promoted from helper to sewing machine operator within a month or two. She was proud to work for Youngone, the biggest foreign investor in the country.

On January 9, Parvin woke up at 5:30 am as usual. After a simple breakfast, at around 7:00 she left home with Nashima. The sisters were a little bit excited. It was their payday. The Prime Minister recently announced that the minimum wage for garment workers would be increased. The sisters expected at least 1,000 taka (US$13) increase each. “Let’s pay off some of the debt and take mother to the doctor”, Parvin said to Nashima. Soon the sisters passed the guards armed with rifles and entered the main gate of Korean Export Processing Zone (KEPZ).

Parvin went into factory #7, Nashima into #6. In factory #7 Parvin made Puma sports shoes. Youngone, the largest manufacturer for The Northface, also makes clothes and shoes for Nike, Puma and many other global sports brands. It’s one of the largest manufacturers in the global sportswear industry.

Inside the factory, 30 workers form a line. Helper’s place is at the end of each line. Parvin’s job is to remove waste thread and glue from shoes. 250-300 pairs of shoes go through her hands every day.

During work, Parvin’s eyes were irritated by toxic fumes from glue. She didn’t use the restroom while working. It takes about four minutes to get to the restroom, which means she has to leave her station for at least 10 minutes. She’d rather hold on until lunch time instead of being yelled at by the line chief or the manager.

Around 11 o’clock, Parvin received her pay slip. The company raised only 700 taka (US$9) from her previous wage, which was 3800 taka (US$49). The numbers didn’t look right to Parvin, and many other workers seemed to feel the same. The company raised basic pay as per the new legal minimum wage, but cut back the allowances. The gross pay was far less than workers anticipated. This was why the company delayed payday for several days without explanation, thought the sisters, to figure out a trick to minimize the wage increase.

As workers were agitated, the managers stopped all the machines. Instead of having lunch, about 5,000 workers gathered in front of the factory. Soon the police showed up. A policeman called two workers among the crowd to a halt and said, “Get back into the factory right now. Get back to work!” One of the workers talked back. “We won’t go back until we receive the right salary.” The policeman started to beat the two workers.

Haruhn, a quality inspector stepped up. “We didn’t break any machine or damage the factory. Why do you beat the workers?”

The policeman said, “So, you are the workers’ representative?” He grabbed Haruhn by his collar, dragged to the guard post, and started beating him with other policemen.

Angry workers surrounded the guard post and started chanting. “Let go of Haruhn! Stop beating Haruhn!” Feeling intimidated, the police fired tear gas. Some workers started to throw brick fragments at the police.

Nashima was terrified. She was scared the flame from the tear gas shell might set fire on her clothes. All she could think at the moment was that she and her sister should go home. Nashima ran into the factory to grab her hijab from the workplace. As a Muslim woman, she didn’t feel comfortable outside without hijab.

As she was getting back out, Nashima heard several gunshots followed by sharp screams. A woman was lying on the ground, surrounded by many workers. She slowly approached the woman. It was her sister, Parvin. There was a bullet hole in her head. Workers stopped a car to send her to Chittagong Medical College Hospital.

But her heart stopped beating before crossing Karnaphuli Bridge, the gateway to downtown Chittagong. Parvin never received her fourth salary.

2. Disappeared workers

There was a huge protest in front of Chittagong Export Processing Zone (CEPZ) in December 2010. Bangladesh government first set minimum wage in 1995, and raised it only three times since then, in 2006, 2010 and 2013, in large increments each time. Many companies tried to minimize the cost increase by cutting allowances, and workers received less than what they had expected. This was why there were violent clashes when the minimum wage was increased. (AFP/Yonhap News)

Top: Streets in front of CEPZ crowded with garment workers getting off work on an evening in March. The Bangladeshi government established eight EPZs for foreign investors. South Korean, Japanese, Chinese investors are running garment factories inside the EPZs. (by Ryu Yi-geun, staff reporter)

Bottom: Youngone shuttle buses parked inside the CEPZ. Unlike most buses in Bangladesh they look clean and intact. They are not for Youngone’s workers, but for its managers. (by Ryu Yi-geun, staff reporter)

A YSL factory gate in the CEPZ. This is the factory where workers were assaulted in December 2010. (by Ryu Yi-geun, staff reporter)

Shuri holds the uniform she used to wear when she worked at the YSL factory as a sewing operator. She witnessed severe assaults on workers in December 2010, and she was fired a month later for participating in the protest. (by Ryu Yi-geun, staff reporter)

According to the workers that the Hankyoreh met, the death toll from the clash in December 2010 was way more than 10, including many Youngone workers. But the local media reported that five people died at most, and none of them were Youngone workers. (AP/Yonhap News)

Three years earlier, it was also the pay slip that brought the bloodshed.

In the morning of December 11, 2010, Mashu, a garment cutter, was in a bus headed to Chittagong Export Processing Zone (CEPZ). Just like the other buses in this country, its body was crumbled on every side and it didn’t have any doors or taillights. CEPZ is about an hour’s drive from KEPZ where Parvin died. Most of Youngone’s factories are concentrated in CEPZ.

Mashu got off at the main gate of CEPZ around 8 o’clock. He walked from there to the factory. Everything was as usual, except the policemen at the guard post. Mashu had never seen policemen at the guard post.

Mashu was not happy with the pay slip he received the previous night. The newly increased minimum wage was applied, but he received 5,400 taka (US$70) which was about 500 taka (US$6.40) less than he expected. But he kept his discontent to himself. He knew well that complainers are likely to be fired.

Mashu cautiously brought up the pay slip at lunch. A friend warned him. “Don’t grumble about the payslip. The general manager did everything he could. Complaining won’t do us any good.” The conversation ended shortly.

A manager invited workers to talk. “If you have any problem with your payslip, come and talk to me. Don’t discuss it with colleagues.” Not a single worker went to talk to the manager.

About an hour later, a woman shouted from the door. “What are you doing here while we are fighting outside! Let’s go out, or I will destroy the machines!” The woman had a stick in her hand. The managers were more alarmed than the workers. They quickly moved to the first floor to stop the machines.

Mashu went outside with friends. Many workers were gathered in front of the next building, which was another Youngone’s factory named YSL. Most of the workers were women. “Our representatives are held inside. They went upstairs to talk to the managers, but they are not coming back. Please help us find them.” They asked Mashu and his friends.

Mashu went inside the building with 10 other workers. Shattered flowerpots were all over the floor, but the machines looked all right. On the 4th floor, Mashu found 3 men inside cabinets in a room. Their bodies were bruised everywhere, and they were barely breathing. Mashu and other workers brought them downstairs.

When Mashu climbed back up to the fifth floor, he discovered a horrific scene. Two men were lying in a pool of blood, trembling. Both men had deep cuts on their wrists and ankles.

Mashu and others made stretchers with sticks and clothes, and carried the two down. Shuri and her colleagues, who had been working in YSL for many years, witnessed those men coming down on stretchers.

Unlike Mashu‘s factory, the atmosphere had been very tense in YSL since the morning. Upset with the pay slip, workers stopped the machines at 9:30. Managers persuaded them to resume working, but the workers stopped working again after lunch. “Who is leading this? Who’s your representative?” A manager yelled with anger.

In every Export Processing Zone, labor unions are illegal, a gift from the Bangladeshi government for foreign investors. Factories with no labor union are not likely to have workers‘ representatives. The manager ordered five male workers in his sight to come upstairs. And those workers couldn’t come back on their feet.

Mashu carried the injured workers to the main gate. He loaded them on CNGs (three wheel taxis) to take them to Chittagong Medical College Hospital. “They might have already been dead when I loaded them on CNGs. I haven‘t heard anything about those workers since then”, said Mashu. Records of those workers were not to be found in Chittagong Medical College Hospital and no one knows what happened to them.

Mashu came to work the next morning. But policemen at the main gate didn’t let him in. His wife, who worked for another South Korean factory was allowed to enter. The police checked ID cards, and blocked every Youngone worker. Miru, a quality inspector at another Youngone‘s factory in CEPZ was blocked from entering as well.

Soon thousands of Youngone workers were left at the gate. It was not a good idea to keep them all together in the same place. Unhappy with the pay slip and angry about the assault against YSL workers the previous day, they became wild. They broke down the main gate of Bangladesh Export Processing Zones Authority (BEPZA) building. BEPZA is the government body that controls EPZs.

Police, the counter terror force ‘RAB’, and Border Guard of Bangladesh (BGB) responded without mercy. Soon after firing tear gas, they started shooting live ammunition and many workers collapsed. A man dropped dead right next to Miru. Miru loaded three dead bodies on a rickshaw van that day. Mashu also loaded three bodies. “I saw many dead bodies carried away by rickshaw vans.” Mashu recalled. Anwar, another Youngone worker found his cousin who also worked for Youngone later that night in the morgue in Chittagong Medical. He saw eight bodies in the morgue including his cousin.

The next day, all the news media reported that at most five people had lost their lives in the CEPZ labor unrest. None of the dead were reported to be Youngone workers. All the bodies Mashu, Miru and Anwar had witnessed were not counted. Mashu is an assumed name of the worker who still works in a Youngone’s factory. Miru and Anwar are real names. They are not employed by Youngone anymore.

Youngone issued a press release in Seoul titled ‘Youngone’s factory in Chittagong attacked by unidentified men’. It said the unrest was due to workers’ misunderstanding of minimum wage increase, and unidentified men from outside broke into the factory to destroy facilities. The press release Youngone issued on January 10 this year, which was a day after Parvin’s death, said almost the same.

On the day Parvin died, Youngone’s stock price dropped by 4.5% in Korea Exchange in Seoul. But it didn’t take a week to recover. No stock analyst was seriously worried about the unrest nor the minimum wage increase. All the competing countries in Asia had wage increase pressure as well, and Bangladesh’s minimum wage was still the lowest even after the increase. Stock analysts forecasted that Youngone, with its massive production capacity and quality competitiveness, would easily shift the increased cost to its buyers. They all recommended buying Youngone’s stocks.

When we met Nashima in March this year, she was still operating a sewing machine in the factory where her sister was killed. She had been crying on her seat for many days after Parvin’s death, said her coworker Sharmin. Nashima said, “It’s scary to work in this place, but I have a bad stomach that asks for food every day.” Now she is the only earner in the family.

The factory is operating normally, as if nothing had happened. After the protest, the company restored the cutback allowances. However, the company reduced overtime. Now Nashima has 8 hours to do what she had done in 10. She said, “I wish we had 15 more minutes for lunch break. 30 minutes is not enough to pray. And it would be nice to use the restroom whenever I want.”

3. Guardians

of the industry

Billboard ads for the ‘Rapid Action Battalion (RAB)’ are easily seen on streets of Dhaka. RAB was formed in 2004 as a counter terror unit. It‘s infamous for brutally suppressing worker protest. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

Many think cheap labor is natural in countries with large labor forces. But Bangladeshi garment workers’ minimum wage, which remains under $100 per month after three decades of industrialization, cannot be solely explained by the laws of supply and demand. The cheap labor that investors benefit from is attributed to brutal violence that oppresses workers’ demands for higher wages and better working conditions.

The streets of Dhaka, the Bangladeshi capital, are always packed with junky cars, CNGs (three wheeler taxi), rickshaws, and beggars. It’s hard to gain speed. There was a little fuss outside the windows of our rental car. A traffic police officer was yelling at a rickshaw puller. It seemed the policeman was ordering the man to move his rickshaw. A second later, the policeman slapped the rickshaw puller in the face with full strength. The frightened man moved his rickshaw right away. Several other rickshaw pullers nearby turned their heads, avoiding eye contact with the policeman. “He’s a nice cop”. Reza, our translator and coordinator said to the foreigners stunned by the scene. “Before the anti torture law, it was easy to see policemen whipping rickshaw pullers.” The Bangladesh parliament passed the anti torture law in October last year.

Poor men from rural villages pull rickshaws. They earn 10-20 taka ($0.13-0.26) a ride. 200 taka a day goes to the garage which owns the rickshaw, and the rickshaw puller keep the rest. 400,000 rickshaws compete in Dhaka. Those who annoy traffic police while trying to occupy a better spot get slapped in the face.

Poor women from villages work in garment factories. They earn a minimum wage of 5,300 taka($69) a month. It barely covers living expenses in the city. Those who raise their voices for higher wages or better working conditions can pay a much higher price than getting slapped.

A Bangladeshi policeman kicks a child during clashes with garment workers in Dhaka on June 30, 2010. (AFP/Yonhap News)

There is a place well known to sailors who visit the Port of Chittagong. It’s called ‘Singapore market’ located in Agrabad district. Big old buildings are full of tiny shops. These shops look shabby from the outside, but inside they are full of new clothes labeled Tommy Hilfiger, GAP, LEVI‘s, Calvin Klein and so on.

The clerk of Azmir Collection welcomed us and forced to try on a Tommy Hilfiger shirt that cost 1,000 taka ($13). When asked if the shirt was authentic, he asserted. “I know people who have connections inside the EPZ. I call them, and they bring me the clothes. They bring what’s left in the factories. So I can’t get same brands every day.”

A Northface winter jacket, likely to be from a factory of Youngone, was in another shop. It’s a jacket no one will need in this country where it hardly ever gets below 10℃, even in the winter. It was 3,500 taka($45). It would be sold at ten times that price in South Korea. A shop owner said that major customers at the Singapore market are Chinese and South Korean sailors.

At the gates of every EPZ, police stop every car and open its trunk to make sure export goods are not smuggled into the domestic market. But ‘mastan’, meaning ‘muscle man’ in Bengali can pass EPZ gates with goods. A lady who has been working as a manager in Youngone for a long time explained what these gangsters do. “They smuggle clothes out of factories. They do a lot of things. It’s an open secret.”

Most of the workers we met were reluctant to talk. A garment worker who helped us arrange meetings with other workers explained why. “Neighbors or colleagues can inform a factory manager who talked to reporters from Korea. Then the manager would send mastans. Between 5 and 10 mastans with weapons would raid the worker’s home at night.”

A worker who is employed in a Korean owned factory in Dhaka called us on the phone a few hours after the interview. “If you crosscheck what I said with the factory management, I can get in big trouble. One of the managers can mobilize about 40 mastans. I might have to leave my village and my job.” Many workers from South Korean-owned factories refused to meet us at all. A labor activist said, “Most of the workers are from different villages. That makes it harder for them to fight together against mastans. That’s why workers fear mastans.” Sidigul Islam, who leads a labor organization in Chittagong said, “Mastans do business with samples, faulty goods and remnants from garment factories. And when the factory management call, they go and threaten workers not to organize any protest. Mastans are connected with local police and politicians. Police won’t do anything even when workers report their crimes.”

Farida Akhter, the executive director of Bangladeshi NGO ‘UBINIG’ has been investigating working conditions in the garment industry since the 1980s. She said, “When you learn about Bangladeshi garment industry, you can‘t miss mastans. They play important roles. In some cases, they instigate workers to start a riot upon the factory owner’s request. They stage a violent situation before the workers are actually ready to organize themselves. Then the police would come in and arrest the workers who are capable of organizing genuine protest. It’s a kind of pre-emptive action.”

The Bangladeshi government established Industrial Police in October 2010 in order to “maintain congenial atmosphere in the factories”, according to the then Home Minister Shahara Khatun. Industrial Police operate mainly for garment factories in four industrial areas: Dhaka, Gazipur, Narayanganj and Chittagong.

Mr. Shahidullah Azim, the vice president of Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers & Exporters Association (BGMEA) said, “Our country doesn’t have enough police forces. Just like the highway police which focus only on highways, BGMEA asked the government to establish police that focus on the garment industry. Sometimes workers start unrest and vandalize factories. We asked the Industrial Police to protect assets and public safety.”

Industrial Police are easily seen in every EPZ. Some are armed with rifles, some with clubs and shields. Mr. Shahidullah explained, “Industrial police take care of both factory owners and workers. They work as mediator when there is unrest. They handle owners‘ misbehaviors as well.”

But the industrial police failed to prevent or investigate the terrible incident in Youngone’s factory in 2010.

Yoon Hee is the owner of a knitwear factory named Haesong in Dhaka. And he is the chairman of the Korean Community in Bangladesh. “The Bangladeshi government established the industrial police in 2010. They stop workers from organizing big protests. Whenever there is a sign of unrest, we make a call and the industrial police are deployed. The chief of industrial police visited Korea twice or so -to buy riot control equipments. He is pro-Korean. He does his best to protect Korean factories.” Mr. Yoon explained.

Another RAB billboard ad in Dhaka. In 2010, RAB was deployed to the CEPZ to suppress the protest by Youngone workers. International human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International condemn RAB as a ’killing squad‘ and call for international pressure to stop its murder. However the South Korean Embassy in Bangladesh asked RAB to protect garment factories owned by Koreans last year. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

This photo printed in The Kyunghyang Shinmun on Nov. 21, 1970 shows the funeral of Jeon Tae-il. Jeon was a garment worker in Seoul, and started the South Korean labor movement to improve working conditions for young women in small garment factories. During a protest on Nov. 13, 1970, he committed suicide by self-immolation while shouting “Abide by the Labor Standards Act! We are not machines!” He was 21 years old.

Yoo, Dong-woo, 65, worked in a garment factory called ’Samwon‘ in the Export Industrial Complex in Incheon, South Korea in the 1970s. The factory was Japanese-invested.

Yoo usually worked 13-16 hours a day. He often worked 24 hours without sleep to meet shipments. Despite long working hours, workers were not properly compensated. Extra allowances for working at night or on holidays were not paid. The Labor Standard Act was neglected. Workers had only two days off per month. “Even two days off were not kept often. We worked almost all year round. Absent workers were fired right away”, said Yoo.

It was a constitutional right to form labor unions, but the military dictatorship which was desperately longing for foreign investment didn’t allow unions inside the Export Industrial Complex. After many twists and turns Yoo managed to organize the first union inside the complex. And Samwon labor union went on its first strike in December 1973. Men from Korea Central Intelligence Agency, the Military Intelligence Command and police took turns attempting to persuade or intimidate Yoo. Police arrested him as soon as the company fired him on a false ground.

Yoo recalled his past as “industrial slavery”. He earned 600-700 won per day, 15,000-20,000 won per month. Female workers earned 300-400 won. “Eating less, spending less was the only way to survive. The wage barely covered room and rice. Instead of dinner women ate late night snacks from the factory. That was another reason why they couldn‘t get away from extra hours or night work.

What happened in South Korea in 1960~1970s is happening now in Bangladesh. Koreans are now the biggest foreign investors in Bangladesh. Just like what the Japanese did in the past, Koreans are making money by taking advantage of low wages and poor working conditions.

Yoo often hears about conditions of Bangladeshi workers in South Korean factories in the news. ”As I was once a garment worker, I feel sorry for the workers. And what’s happening there feels pathetic. It makes me really angry sometimes“, he said. (by Ryu Yi-geun, staff reporter)

The international cricket tournament ICC World T20 was held in Bangladesh in March. Bangladesh was a British colony until 1947, and cricket is the most popular sport among its people. On game days, traffic congestion is worse than usual. In the heavy traffic, our rental car was stuck next to a black pickup truck. Muscular men in black hoods, black sunglasses, black uniforms were in the truck. One of the men with an automatic rifle on his shoulder leaned down to look inside our car.

“Hands off your camera. Don’t look at him!” said Reza in a low but desperate voice. Our driver Ajimul also shut his mouth and fixed his eyes to the front. For about three minutes until the black pickup truck turned away from us, nobody in the rental car said a word.

The men in black were members of the Rapid Action Battalion, commonly called RAB. RAB was formed in 2004 to support the ’war on terror‘ led by the U.S. and the UK. Elite members of military, police and various law enforcement agencies joined the RAB.

On July 26, 2008, Novera Khatun, an 80 year old woman stood in front of Jhenidah Press Club in Dhaka. This is the place where NGOs, political parties, labor unions hold press conferences. The old woman begged the government to save her son from “crossfire” and prosecute him instead if he had committed any crime. Her son Mizanur Rahman Tutul, a physician, was arrested by the RAB the previous day.

In our earlier interviews with activists, we were confused by the word “crossfire”. According to Merriam-Webster dictionary, it’s a noun meaning “firing (as in combat) from two or more points so that the lines of fire cross”, or “a situation where in the forces of opposing factions meet, cross, or clash”.

In Bangladesh, this word gained new meaning. Many people were shot dead a few days after being arrested by the RAB. In many cases their bodies showed signs of beating or torture. RAB issued official statements that the criminal was killed in crossfire. According to RAB, 622 people were killed in crossfire from 2004 to 2010. Human rights organizations claim there are much more victims of crossfire. RAB gave the word ‘crossfire’ a new meaning. It became a verb meaning ‘to execute someone without legal procedures’.

Mizanur Rahman Tutul, the physician was “crossfired” the day after the old mother’s press conference. He was accused of leading an outlawed communist party.

Taking care of workers’ protests is a part of RAB‘s mission. RAB was deployed in CEPZ in December 2010 when many Youngone workers were killed. “First they intimidate with threats. Then they start beating. After that they fire blanks, and then they fire live ammo. They are horrific”, said Mashu, the garment cutter in a Youngone’s factory. International human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch(view) and Amnesty International condemn the RAB as a “killing squad”.

At the end of 2013, the South Korean Embassy in Bangladesh called for help from RAB and DGFI (Directorate General of Forces Intelligence). The embassy asked the RAB and DGFI to protect South Korean-owned factories when unrest occurred in multiple locations at the same time, because then local police and industrial police might not be able to control the situation. Receiving an affirmative answer, the embassy informed factory owners to call for help whenever they had trouble.

Historically speaking, the garment industry had been relying on violent force of state and capital since its beginning. In the 18th century, a number of inventions that brought cotton gin, spinning and weaving machines made cotton manufacture a mechanized industry. The explosive growth of production capacity called for enormous supply of raw cotton. Only America had large enough land to meet the demand. But land doesn’t grow crops by itself. Raw cotton was grown by slave labor of African-American slaves in the plantations of the southern states.

In the early 20th century, young women from rural areas filled the garment factories in the cities of the West. They had to endure low pay and long working hours. Attempts to take collective action were often frustrated by police or other state institutions.

It was natural that the most of 15,000 women who joined the historical march through New York City in 1908 demanding shorter hours and better pay were garment workers. International Women’s Day is celebrated on March 8th every year to commemorate this march.

Three years after the march, a fire broke out at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York City. The doors on each floors of the factory were locked from outside to prevent workers from stealing or taking unauthorized breaks. More than 140 women, most of them in their teens or twenties, died. This tragedy drew significant attention to working conditions of women in the West.

After the two World Wars came the golden age of capitalism. And the distance between consumers and manufacturers increased drastically. Post-war Japan became the production base of garments for the Western consumers, followed by South Korea.

In the 1960s and 1970s South Korean female garment workers were faced with deadly working conditions. On Nov. 13, 1970 Jeon Tae-il, a male garment cutter and a pioneer of South Korea’s labor movement, committed suicide by self-immolation in protest of the poor working conditions in the sweatshops of Seoul. Physical and sexual violence against female garment workers were common. The military dictatorship trampled attempts to form labor unions in the nation’s biggest export industry. Gangs hired by factory owners and police worked together to suppress labor disputes. Factory owners and state institutions worked together to make blacklists of labor activists in order to keep them out of factories.

Western society was indifferent to what was happening in the factories on the opposite side of the globe. The Cheonggye Garment Labor Union, which was the legacy of Jeon Tae-il, was ordered to be dissolved by the mayor of Seoul in 1981. The union occupied the Seoul office of the U.S based labor organization AAFLI (Asian-American Free Labor Institute) in the hope of getting attention from the outside world. The union requested a meeting with AAFLI‘s executive director Morris Paladino who was visiting Korea at the time. Also at the time, South Korean President Chun Doo-hwan was visiting the US at the invitation of President Ronald Reagan. Mr. Paladino refused the request for a meeting. Soon the police raided the office. 11 leaders were detained, and the union collapsed.

In 1980’s, Korean workers’ wage began to increase sharply as the country’s democracy was enhanced. Global brands moved their production base from Korea to China. This is when Mr. Sung Kihak, who founded Youngone in 1974, started moving his factories from Korea to Bangladesh.

Manufacturers shifted from China to Vietnam, Malaysia, Sri Lanka. After that, they came to Bangladesh, India, Cambodia and Myanmar. Meanwhile, fast fashion brands such as GAP, H&M, ZARA, UNIQLO dominated the global garment industry.

Cambodian riot police beat a striking garment worker in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, Jan. 3. On that morning, the Cambodian police and military opened fire on garment workers, who were protesting on the outskirts of the capital Phnom Penh, leaving at least five people dead. (Xinhua/Newsis)

Phrum Pirom, 22, and his sister fell asleep on a bed in Khmer Soviet Friendship Hospital in Phnom Penh on Jan. 15. Pirom was shot in the leg during a protest for wage increases on Jan. 2. Pirom worked in a South Korean owned garment factory in Canadia Industrial Park. (by Kim Myung-jin, staff photographer)

In the age of fast fashion where clothes are cheaply made and quickly consumed, the rights of garment workers are neglected more than ever. Governments in Third World countries seem not to hesitate to shoot their own garment workers to “protect the industry”. On January 9, garment worker Parvin Akter was shot dead in Bangladesh. A week earlier at least five garment workers were shot dead by an airborne unit in Cambodia. KTNC Watch, a joint network of NGOs, lawyers and labor unions monitoring Korean companies abroad pointed out in its field investigation report that “The forces ruthlessly assaulted unarmed workers even in front of the UN office. It‘s definite proof that the Cambodian government puts the garment industry’s benefit before workers’ human and labor rights”.

Faced by overwhelming power, workers accept their fate. Majeda Katun, Parvin’s mother, couldn‘t stop sobbing while telling us about her daughter’s death. But she concluded the conversation by saying “Parvin was unlucky.” Mohamed Haruhn, the quality inspector who was beaten by the police, which triggered the angers of other workers in KEPZ this January said, “Neither the company nor the police apologized. But I don’t complain. After the protest the company raised our wage. Maybe that was an apology.” Shohidul, a sewing machine operator at Youngone who was injured by a bullet to the head, said, “We gained everything we wanted. So we keep quiet.”

Masum returned to Bangladesh and became a labor activist after living for 10 years as a migrant worker in South Korea. He said “Some say that Bangladeshis are the happiest people in the world. But I disagree. I don’t think they are happy. They just give up easily.”

Thanks to cheap labor in Bangladesh, controlled by brutal forces, consumers in other parts of the world wear cheap clothes. An agent who works as a middleman between British buyers and Bangladeshi factories said “In London, a pack of cigarette costs 7 pounds ($11.3). A T-shirt costs 5 pounds. 4 pairs of boxer shorts are sold at 4 pounds. Garments are the only products that get cheaper year after year.”

4. Safe business

In the morning of Apr. 24, 2013, the Rana Plaza building located in Savar on the outskirts of Bangladesh‘s capital Dhaka collapsed, killing at least 1,129 garment workers. 8 years earlier, Spectrum Sweater factory building collapsed, killing 62. Since 1990 there have been 23 major fire and building collapse incidents in Bangladesh, taking lives of more than 1,750 garment workers. (Xinhua/Newsis)

Many lives are lost but no one is responsible.

Garment factories in Bangladesh are deadly job for the workers,

safe business for the owners.

A picture of Poly and fliers hanging on the wall of Dhalia‘s house. The family printed these fliers after the collapse to hand out to rescuers in the hope of finding Poly. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

Dhalia survived the collapse with light scratches and bruises. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

Dhalia lives with her parents and three sisters in a single room in Savar. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

Dhalia’s whole family gathered in front of the father‘s grocery store. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

4 - 4

<

>

Dhalia was working inside the Rana Plaza building at the time of collapse. She survived miraculously, but her sister Poly didn’t. In an interview at her house in Savar, Dhalia recalls the collapse. On the floor is a photo of Poly. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

The High Court building in Dhaka was built as the governor general‘s house in 1905 when Bangladesh was a British colony. The judicial system of the country had long been blamed for its incompetence in punishing crimes committed by the rich and privileged. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

A rickshaw passes by the abandoned Tazreen factory in Ashulia. The factory caught on fire on Nov. 24, 2012, leaving at least 112 workers dead. After the accident, the factory has been closed and locked down by police. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

The headquarter building of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) by Hatirjheel Lake in Dhaka is a symbol of privilege and impunity for its members. This 15-story glass tower was built violating many environmental laws and building codes in 2008. The High Court ordered demolition of the building in 2011, but nothing has happened so far. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

Sumaya’s father waits for the imam to pray for his late daughter in his house in Nischintapur, Ashulia. Sumaya, a former Tazreen worker escaped from the fire, but was diagnosed with a rare type of cancer. She died on Mar. 21, at the age of 16. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

Ruins of Rana Plaza is cleared now. There are fences around the site. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

On 24th day of every month, families of Rana Plaza victims gather in front of the site. They demand compensation for the victims and punishment of those responsible for the deaths. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

On 24th day of every month, families of Rana Plaza victims gather in front of the site. They demand compensation for the victims and punishment of those responsible for the deaths. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

On 24th day of every month, families of Rana Plaza victims gather in front of the site. They demand compensation for the victims and punishment of those responsible for the deaths. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

On 24th day of every month, families of Rana Plaza victims gather in front of the site. They demand compensation for the victims and punishment of those responsible for the deaths. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

On 24th day of every month, families of Rana Plaza victims gather in front of the site. They demand compensation for the victims and punishment of those responsible for the deaths. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

On 24th day of every month, families of Rana Plaza victims gather in front of the site. They demand compensation for the victims and punishment of those responsible for the deaths. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

On 24th day of every month, families of Rana Plaza victims gather in front of the site. They demand compensation for the victims and punishment of those responsible for the deaths. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

On 24th day of every month, families of Rana Plaza victims gather in front of the site. They demand compensation for the victims and punishment of those responsible for the deaths. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

On 24th day of every month, families of Rana Plaza victims gather in front of the site. They demand compensation for the victims and punishment of those responsible for the deaths. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

Human bones are still found occasionally in the Rana Plaza site. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

A boy collects scrap metal at the Rana Plaza site. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

Bones that seem to be human are collected in a hole in the Rana Plaza site. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

A boy collects scrap metal at the Rana Plaza site. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

A policeman chases out boys collecting scrap metal from the Rana Plaza site. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

15 - 15

<

>

The name of the village Sumay lived in is Nischintapur, meaning ‘place of no worries’ in Bengali. More than 100 residents of this village died in the Tazreen fire. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

The name of the village Sumay lived in is Nischintapur, meaning ‘place of no worries’ in Bengali. More than 100 residents of this village died in the Tazreen fire. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

The name of the village Sumay lived in is Nischintapur, meaning ‘place of no worries’ in Bengali. More than 100 residents of this village died in the Tazreen fire. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

On Mar. 21, three days after Sumaya‘s death, families, neighbors and labor activists gathered at her house to pray for her. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

On Mar. 21, three days after Sumaya‘s death, families, neighbors and labor activists gathered at her house to pray for her. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

On Mar. 21, three days after Sumaya‘s death, families, neighbors and labor activists gathered at her house to pray for her. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

On Mar. 21, three days after Sumaya‘s death, families, neighbors and labor activists gathered at her house to pray for her. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

7 - 7

<

>

There was commotion in front of the factory building on the morning of Apr. 24. Dhalia came to work after three days of leave. She was told over the phone the previous day by her line leader that the factory was closed because cracked walls were being repaired. She and the other workers were not sure whether the factory would be open, but most of them showed up at 8 am in the fear they might be penalized for being absent. But they hesitated to enter the building. They didn’t feel safe.

“If you don’t go in now, you won’t get the attendance bonus,” Imuran, the production manager of Phantom Apparels, yelled at the workers. Most garment factories in Bangladesh give attendance bonuses of 200 taka (US$2.60) a month so that workers aren’t absent or late. To receive this bonus, Dhalia and her sister Poly hurried their steps for 30 minutes every morning. On days when the sisters overslept, they took rickshaw for 15 taka.

“1,000 taka can be deducted from your pay as penalty for being late!” Imuran yelled again.

The building owner Sohel Rana appeared. “The building is safe. There were little cracks, and the engineers fixed them yesterday. There is no problem now. Get in!” Factory owners showed up with men that look like mastans.

“A big shipment is due soon. Get to work now!” Jamal, the managing director of Phantom Apparels shouted.

Four days ago, Dhalia and Poly received three days leave after working late on Saturday. The sisters and their father headed to their hometown in Netrokona to meet Poly’s possible bridegroom.

It was their first visit in five years. The family left their hometown for Savar, a suburb of Dhaka, in 2008, when the father’s furniture factory went out of business, leaving the family with debt of 150,000 taka (US$2,000).

One day after the family arrived in Savar, Dhalia started working in a garment factory with her aunt. She was a fast learner. She worked a sewing machine after only one month as a helper. Her first payment was 2,000 taka (US$26), but it rose steeply as she moved to different factories. At Phantom Apparel, she earned 9,000 taka (US$116) a month. Poly joined Phantom Apparel in 2010. “With a blessing from Allah” her father, who started selling groceries on the streets, managed to open a stall in the market.

After four years of hard work, the family managed to pay off all the debt. Then it became time for the sisters to get married. The candidate for Poly’s bridegroom was a soldier from her hometown. Soldiers who can apply for UN missions and earn lots of money are favored in Bangladesh. The soldier who had only seen Poly in a photo liked her more after actually meeting her.

After three days of leave the sisters returned to work. The sisters, along with 3,000 workers, were forced into the building where all the shops and bank had already evacuated. On the fourth floor, the sisters sat about 25 meters away from each other in the ‘line C’ where 130 workers work together. They started working on T-shirts for Primark, a brand based in England.

Shortly after, all the sewing machines came to a stop. It was a blackout. Due to poor infrastructure, there are 3-4 blackouts a day in Bangladesh. The generators on each floor started running with loud noise and vibration.

It was about five minutes after the factory resumed operation. Dhalia was deafened by a thundering noise and blinded by thick gray dust.

When Dhalia recovered consciousness, she found herself lying outside. From head to toe she was aching and covered with dust. Her arms and knees were bleeding. When she looked up, she saw the eight story building collapsed. People around the wreckage who noticed Dhalia ran toward her to take her to hospital. She pushed away the hands of rescuers. She crawled around the ruins crying “Poly, Poly!”

The High Court building in Dhaka, with its prominent central porch under a triangular pediment supported by Corinthian columns, is a fine example of European Renaissance style. It was built as the house of the governor of East Bengal (currently Bangladesh) and Assam (northeast India) in 1905. The Western world took tea and jute at cheap price from this land from 1858 until 1947. Now they are taking cheap clothes made by the cheapest labor force in the world.

Four days after the Rana Plaza collapse, three female labor rights activists including Saydia Gulrukh visited the High Court. They had been helping the victims of the Tazreen factory fire, which happened five months earlier. Seeing another catastrophe killing more than a thousand people, they were convinced that the only way to stop these kinds of disasters from happening again is to make sure those responsible are brought to justice,

On Nov. 24 2012, five months before the collapse, Tazreen factory in Ashulia caught on fire. The nine story factory building was originally granted a permit to be a three story building. The first floor was packed with flammable fabric. There were no emergency exits. The steel doors on every floor were locked from outside. The fire quickly spread from the first floor up to the fifth floor. Workers strong enough to break steel barred windows or ventilation fans jumped and got injured. At least 112 who couldn’t escape died in the fire.

The female activists filed a petition to the High Court seeking warrants for arrest and punishment of the Tazreen factory owner, Delwar Hossain. As a result of the petition, Delwar appeared in court for the first time on May 30, 2013, six months after the fire. A former Attorney General of Bangladesh defended Delwar as his lawyer. Surrounded by bodyguards, Delwar pointed his finger at Saydia and her friends and said, “You are going to send me to jail? You can’t do anything to me.”

He was not bluffing. He’s a member of Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA). Rubana Huq, the managing director of one of the country‘s biggest garments manufacturer Mohammadi Group, said “Delwar is a powerful man. He’s very close with the high-level guys at BGMEA. You see, nothing happened to him right after the fire.”

Ashulia Police filed a case accusing unidentified people a day after the fire. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina assured prompt and transparent investigation. However the investigation made little progress for the next five months.

In this country, where garments account for 80% of all exports, BGMEA and its members enjoy lots of power. The headquarters by Hatirjheel Lake demonstrates BGMEA‘s power. This 15-story glass tower was built in 2008 on illegally obtained land, violating many environmental laws and building codes. The High Court ordered demolition of the tower in 2011, but it still stands.

In 2013, 29 of 300 members of Bangladeshi parliament officially owned garment factories. Local labor organizations presume more than half of the MPs are involved in the garment industry either directly or indirectly. Farida Akhter of ‘UBINIG’ said “Many politicians and high ranking government officials are connected with the garment business. Most local news media have a stake in the garment industry.”

The High Court urged investigation after the petition by Saydia and her friends, but it didn’t make much difference. On December 22 2013, 13 months after the fire, police finally pressed homicide charges against Delwar and his wife. But Delwar had already absconded at that time.

In the morning of Feb. 9, Saydia was escorting Sumaya, a 16 year-old Tazreen fire survivor, to the hospital. Sumaya received basic surgery for trauma to her face which she sustained when she jumped out of the burning building. But after the surgery she began to get nosebleeds. Her right eye began to bulge and lose vision. Later she was diagnosed with a very rare type of cancer, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. While waiting to see the doctor, Saydia received a phone call from a friend who was a court reporter. He told Saydia that Delwar appeared in court, probably to get bail for the arrest warrant issued 2 months earlier. Saydia quickly made phone calls to activist friends, and took a rickshaw to the court.

About a dozen lawyers were surrounding Delwar in the courtroom. One of the lawyers picked up colorful jerseys and waved them over his head. Those were jerseys for national soccer teams of Brazil, Argentina and Italy. The lawyer said “Mr. Delwar Hossain’s Tuba group won the contract to supply these jerseys for the FIFA World Cup 2014 in Brazil. If he gets arrested, Tuba group won’t be able to make the shipment. That will give Bangladesh a bad name.” Another lawyer appealed why only Delwar had to be arrested while none of the owners had for previous factory fires. Some argued that the managers were responsible for the fire, not Delwar.

Meanwhile more than 50 reporters swarmed the courtroom. Articles on the hearing came online immediately. The voice of people outside chanting ‘Punishment for the owner’ came through the courtroom walls.

After nearly three hours of the hearing, Senior Magistrate Tajul Islam finally announced the bail petition’s rejection. Saydia and many other activists in the courtroom cheered. Delwar was sent to jail 15 months after the fire. When Saydia came out of the courtroom, hundreds of people were still chanting ‘Punishment for the owner!’

Saydia later recalled “We went to the High Court because there are too much corruption within the police and the lower court. But honestly, I didn’t believe Delwar would be sent to prison. Since the Saraka Garments factory fire in 1990 thousands of workers died in so many fires and collapses. But none of the owners were ever brought to justice.”

However, it would be hasty to anticipate that the culture of impunity for factory owners is changing.

Sohel Rana, the owner of Rana Plaza building was arrested four days after the collapse near the border while attempting to flee to India. The local leader of ruling Awami League built a building neglecting all construction laws. On Mar. 24, the court granted bail to Sohel in the case filed against him for violating construction laws. Sohel is trying to get bail in other cases as well. Two factory owners who had forced their workers into the building on the day of collapse were bailed out long ago. On Aug. 5, Delwar Hossain was granted bail, walked out after six months of imprisonment. BGMEA has been persistently seeking bail for Delwar Hossain and Sohel Rana.

Dhalia printed thousands of copies of Poly’s photo which was originally taken to show to bridegroom candidates. Dhalia and her family and friends handed out the photos with their phone numbers written to the rescuers at the hospital, the site of the collapse and other places. Eight days after the collapse, Poly’s body was found in the ruins of Rana Plaza.

Compensation for victims in Bangladesh usually comes late. Until a year after the collapse, Dhalia‘s family received 20,000 taka (US$260) from the local government for the funeral costs, 100,000 taka (US$1,300) in emergency allowance from the Prime Minister’s office and 45,000 (US$580) taka from Primark, the global brand for which the sisters were making shirts at the time of collapse. Compensation for Poly‘s death has yet to come.

Even the death toll is still not confirmed. Taslima Akhter, a labor activist and photographer, said, “There are many victims whose bodies haven’t been found. The Ministry of Labour, police, and the military all have different numbers. 291 bodies were buried without being identified. A committee to finalize the amount of compensation for the dead was formed, but it’s taking forever to come to a conclusion.”

Two years have passed, but compensation for the Tazreen fire victims hasn’t been completed either. At least 112 died, but only the families of the 99 workers whose bodies were found received 700,000 taka (US$9,000) each. In the fire that took 17 hours to extinguish, many bodies burned to ashes. 13 workers were later identified by DNA analysis of the ashes, but their families haven’t received compensation yet. Saydia who’s been interviewing the survivors and the families of missing workers for the last two years believe between 12 and 23 more workers had died in the fire. Advocate Asaduzzaman who represent the victims is arguing that the compensation should be much bigger than 700,000 taka, since the fire was more of a case of gross negligence than a mere industrial accident.

Sumaya, the young Tazreen survivor died of a tumor on Mar. 21 without receiving any compensation. Dhalia, who miraculously survived the Rana Plaza collapse but whose sister didn’t, started working at another garment factory in September last year. With to the minimum wage increase, she earns about 10,000 taka (US$130) a month - 1,000 taka more than what she earned in Phantom Apparel. In the town where at least 1,129 died and more than 2,500 were injured in a day, her father’s grocery shop is not making as much money as it did before.

5. Buyers’ hotel

Garment workers at work in a factory in Savar. Western consumers were shocked with the Rana Plaza collapse, which killed more than 1,100 workers. They condemned global fashion companies for neglecting the safety and lives of Bangladeshi workers. Global apparel companies began safety inspections in factories in Bangladesh. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

More than 1,100 lives were lost in an instant. They were the lowest-paid workers in the world.

Global fashion companies expressed unprecedented concern for workers in Bangladesh.

But some say it didn’t last long.

Top: Crowded with people, cars and rickshaws, the streets of Dhaka are always noisy and dusty. The five star hotel Westin Dhaka is a rare peaceful place in the city. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

Middle, Bottom: The Westin Dhaka hotel is guarded by armed policemen and security services. Most of the hotel guests are people who work for global fashion companies. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

Wal-Mart broke off its business relationship with Simco due to illegal subcontracting with Tazreen in 2012. Simco used to run 14 lines but now operates only 4.

Wal-Mart broke off its business relationship with Simco due to illegal subcontracting with Tazreen in 2012. Simco used to run 14 lines but now operates only 4.

Wal-Mart broke off its business relationship with Simco due to illegal subcontracting with Tazreen in 2012. Simco used to run 14 lines but now operates only 4.

Muzaffar Siddique, the managing director of Simco, argued that Wal-Mart granted permission for the subcontract, but Wal-Mart dismissed his claim.

4 - 4

<

>

Dhaka is not the most pleasant city in the world. First-time visitors are alarmed by its noise. Drivers of junky cars and buses honk every other second to make their way through crowded streets. Dust from dirt roads and smoke from garbage fires in backstreets make breathing difficult. Many beggars appeal for money, with all kinds of disabilities. It’s awkward to either meet or avoid their eyes. And the mosquitoes seem to be more attracted to foreign blood.

There are very few sanctuaries where you can escape the unpleasant environment. The Westin Dhaka Hotel, located in the center of Gulshan area, is one. If you pass the guards who sweep the bottom and trunk of your car, the sharp eyed policemen armed with rifles, the metal detector and x-ray scanner, you enter the exceptionally quiet, clean, luxurious space.

One night stay in this five star hotel costs around $400, equivalent to 3 months salary for an experienced sewing operator in Bangladesh. Most of the hotel guests who spend that amount of money work for the global fashion brands, the buyers.

Last February, GAP held a meeting in the hotel. People from the San Francisco headquarters, from the Dhaka liaison office and the local factory owners gathered in a conference room. People from GAP began the meeting with the usual compliment, saying the factories had been doing fine and they were looking forward to another good year.

A young owner raised his hand and politely asked a question, in fluent British-accented English, that every other owner had in mind. “Could you raise our price?”

The Rana Plaza collapse killed at least 1,129 people and brought huge change in Bangladesh. The western consumers who were angry and upset with the tragedy initiated the change.

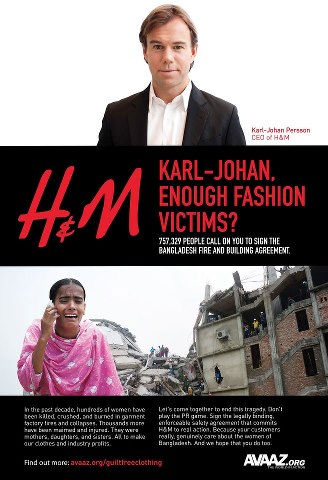

The Swedish brand H&M is the biggest importer of products made in Bangladesh. Swedish citizens demonstrated their anger with a poster that contrasted smiling face of Karl-Johan Persson, the CEO of H&M, with a crying Bangladeshi woman in front of the ruins of Rana Plaza.

Consumers in other western countries reacted similarly. There were few fashion brands that didn’t source from Bangladesh. Ethical consumers harshly blamed global brands for neglecting the lives of Bangladeshi workers while profiting from their cheap labor.

H&M signed on ‘The Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety (ACCORD)’ with international labor organizations. Zara, Marks & Spencer, Carrefour and many other European companies followed. GAP, Wal-Mart, Northface and some other North American companies formed ‘Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety (Alliance)’.

The buyers collected money and started safety inspections on their suppliers in Bangladesh. ACCORD and Alliance demanded that factories install fire safety facilities such as fire-proof doors, emergency exits, and sprinklers. Otherwise the buyers would not place orders. For the first time in history, global buyers collectively engaged to improve factory safety.

Buyers also showed their support for a minimum wage increase in Bangladesh. The Bangladeshi government raised garment worker’s minimum wage from 3,000 taka (US$39) to 5,300 taka (US$68) in January, but some factory owners felt that was a financial burden.

David Savman, the country manager of H&M liaison office in Dhaka sent an e-mail to its suppliers last December. “We believe that it is positive for the textile industry of Bangladesh and support this increase… H&M also acknowledges that this means increased costs and we will therefore revise all prices on placed orders that are affected… For all orders that will be placed from week 51 onward we will negotiate and add the new minimum salary”, he wrote. Many other buyers sent similar messages.

Despite these new changes, there is one thing the buyers won’t change. That is their position on illegal ‘subcontracting’. For many years the buyers blamed subcontracting for accidents in their supplier‘s factories, an easy way to dodge social condemnation themselves.

The Tazreen fire is a good example. The workers were producing shorts for Wal-Mart. Wal-Mart first denied any relationship with the factory. However clothes with Wal-Mart label were soon found in the ruins. Then Wal-Mart blamed its supplier Simco for illegally subcontracting to Tazreen. Simco argued Wal-Mart had granted permission for the subcontracting, but its claim was dismissed. Simco, which had been supplying Wal-Mart for over 20 years, was put on Wal-Mart’s blacklist. Wal-Mart even refused to clear the previous orders from Simco that had already arrived at the Port of Los Angeles. Simco, which was running 14 lines before the Tazreen fire, now runs only 4 lines. About 1,500 workers lost their jobs.

The buyers‘ logic is that they can make sure the factories don’t have any problems if they are directly contracted, but if the initial contractor secretly subcontracts to another factory, it‘s impossible to monitor. After the Rana Plaza collapse, buyers have emphasized their ’zero tolerance‘ of subcontracting even more. However, factory owners in Bangladesh say it’s hypocrisy.

Rubana Huq, the Managing Director of Mohammadi Group said, “Buyers know their suppliers‘ exact production capacity. Let’s say my factory can produce 100,000 pieces of one style. If the buyer orders 500,000 pieces, he should ask who will produce 400,000 of those pieces. But buyers often don‘t ask those questions. They don’t want to know more.”

Every global buyer has a set of standards on building safety and labor conditions for suppliers. They contract with factories that meet their standards. These factories are often called ‘five star factories’. The five star factories source orders from global buyers. The orders are often far larger than their capacity. They subcontract the over-sourced orders to ‘shadow factories’, of which facilities, wages, working conditions are worse than the five star factories. Thanks to these shadow factories, global buyers source products at cheaper prices. However since the buyers didn‘t sign any contracts with those factories, they are not responsible for what happens there.

After the Rana Plaza collapse, Swedish citizens demonstrated their anger with a poster that contrasted the smiling face of H&M CEO Karl-Johan Persson, with a crying Bangladeshi woman in front of the ruins of Rana Plaza. The poster asks ”enough fashion victims?“ Forced by angry consumers, global fashion companies either signed on Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh or joined the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety.

As of April, 4,417 factories were registered at Bangladesh Garments Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA). Though there are no official statistics on unregistered factories, local businessmen estimate around 2,000 unregistered factories are in operation. Unregistered factories subcontract orders from registered factories. Subcontracting occurs between registered factories as well. Subcontractors often subcontract again to other factories. Throughout the process, facilities deteriorate, workers’ wage decrease, and transparency is lost.

The Center for Business and Human Rights at New York University Stern School of Business published a report(view) titled ‘Business as usual is not an option: Supply chains and sourcing after Rana Plaza’ last April. The report concludes that indirect sourcing (subcontracting) has become an essential feature of the garment sector in Bangladesh, and is likely to be important in the future. The report warns that efforts to improve the industry are not likely to succeed without addressing this system.

Muzaffar Siddique, the managing director of Simco said, “There was subcontracting in the past, it’s here now, and it will continue in the future.”

In February, GAP informed its employees that it would raise its minimum hourly rate from $7.25 to $9 this year and to $10 next year for its U.S. workers. A few weeks later president Barack Obama made an unannounced stop at the Gap store in midtown Manhattan, to spotlight the company’s new policy.

“It’s not only good for them and their families, it’s also good for the entire economy”, Obama said as he bought GAP sweaters for his wife and daughters.

However, wage increases for Bangladeshi workers only mean increase of cost. The factory owners who were waiting for an answer from GAP in the hotel’s conference room in Dhaka last February were soon disappointed.

A participant of the meeting said on condition of anonymity, “GAP’s answer was that our productivity needs to be increased, not the price.”

Another participant said “Trousers for example, the price we get from GAP is $8-9. Those trousers are sold for $30-40 at American stores. How can they tell me to lower the price when my total labor cost has increased by 40%? It‘s unreasonable pressure. Nobody in GAP understands us. It looks like everybody is eager to show performance by cutting the price.”

A factory owner who supplies to both GAP and H&M said, “Yes, H&M raised prices, but only for a while. The next season, prices went down to where they had been or even below. What they said about raising price was all for show, for the media.”

“Buyers are two-faced”, said Fazlul Hoque, former president of Bangladesh Employers Federation. “They always say that they welcome the wage increase. But when we ask them to share the costs, they refuse. They say, we know about your wage increase but Vietnam and Cambodia offer lower prices. That’s a very common dialogue. In Vietnam or Cambodia, they might say Bangladesh offers lower prices. Competition is too intense, not just between different countries but also within Bangladesh. Buyers always take advantage of the competition.”

6. Earning surprise

Youngone‘s office building in Seoul. The biggest buyer of Youngone is the U.S. based fashion company VF which owns Northface and about 20 more brands. Youngone manufactures about 40% of Northface products sold around the world. Its yearly sales are about US$1.4 billion. Youngone is one of the 100 largest South Korean companies in terms of market capitalization. (by Lee Jeong-a, staff photographer)

At the western mouth of the Karnaphuli river is the Port of Chittagong. This is where clothes made in Bangladesh are shipped abroad. (by Ryu Yi-geun, staff reporter)

Majeda Katun holds picture of her daughter, Parvin, who was killed by police gunfire during a protest for higher wages at the Korea Export Processing Zone (KEPZ) last January. (by Ryu Yi-geun, staff reporter)

Youngone‘s office building on a hill called ’Mallijae‘ in Seoul. (by Lee Jeong-a, staff photographer)

The Karnaphuli River runs through Chittagong into the Bay of Bengal. West of the river’s mouth is the Port of Chittagong, from where clothes made in Bangladesh are shipped abroad.

Long ago, the international trading port was on the other side of the river. The ancient port is now inside the Korea Export Processing Zone (KEPZ) owned by Youngone. The development began in late 1990’s, but it’s still mostly unoccupied, with only 4-5 factories operating. Bangladesh, a country with a large population and small amount of land, sold this plot, equivalent to about 700 soccer fields, to a foreign investor.

Parvin Akter, 21, a helper in a factory in the KEPZ, was shot and killed by police during the protest on January 9. Traces of Parvin were erased quickly. She underwent an autopsy at Chittagong Medical College Hospital, but her sister Nashima, who brought her body, was not informed of the autopsy.

Parvin’s body was brought back home around midnight. The village foreman and men probably from Youngone urged burial, saying the body might decompose. Muslims are buried shortly after dying, but burial in the middle of the night is unusual.

Parvin was buried beside the ‘parrots pond’ near their home. When they were children, the sisters used to swim and do laundry in the pond where parrots often visited. When big trees around the pond were cut down many years ago, the parrots left and never came back.

Several days after the funeral, people from Youngone came to Parvin’s home and took all her documents related to the factory, including her ID card and payslip. The only evidence left showing Parvin’s existence is the blurry picture of her bleeding from the head after the shooting .

4,500 taka (US$58) was printed on the last pay slip Parvin received. It was far less than she expected after the minimum wage increase. That was because the company cut down allowances.

Parvin’s colleagues received properly increased salary several days after her death. Parvin didn’t receive her salary for December, but her family received compensation of 600,000 taka (US$7,800) from Youngone. It’s a fortune the family could never have imagined. Parvin’s mother Majeda Katun let one of her acquaintance take care of the money. She was only told that the money is in a bank account that earns no interest. “My daughter calls me mommy, but money doesn’t”, cried the mother. Nowhere in the world can money replace a daughter.

There is a village called Bondor Bazar between their house and the factory. It has been an international trading post since ancient times. Nowadays the village is home to garment workers from different parts of the country.

In March, the Hankyoreh conducted a little survey of 10 Youngone workers in this village, and found out their average monthly pay was 7,350 taka (US$95). Their average length of employment was around 2 years.

On the hill called ‘Mallijae’ in Seoul, you can find an artificial rock climbing wall with the logo of Northface on it. Next to the rock wall is the eight-story Youngone building. Most of the building is occupied by the export department. There is a store on the first and second floors. It sells Northface and some other sports brands Youngone has the right to within Korea.

In the morning of Mar. 14, Youngone held its annual shareholders meeting in this building. Among the several items shareholders discussed was the annual salary limit for its executives. It was 4 billion won (US$3.8 million) for eight executives including three outside directors.

According to the official data, Sung Ki-hak, the owner of Youngone group, received 1.6 billion won from Youngone Trading and 1.9 billion won from Youngone Holdings in salary for 2013. Sung owns 17% of Youngone Holdings, so he also received 1.15 billion won (US$1.09 million) in dividends. Salaries or dividends from dozens of unlisted companies in South Korea, Bangladesh, China, Vietnam, El Salvador are not open to the public. Youngone claimed that though Sung acts as an executive in companies in Bangladesh, he’s not receiving remuneration from these subsidiaries.

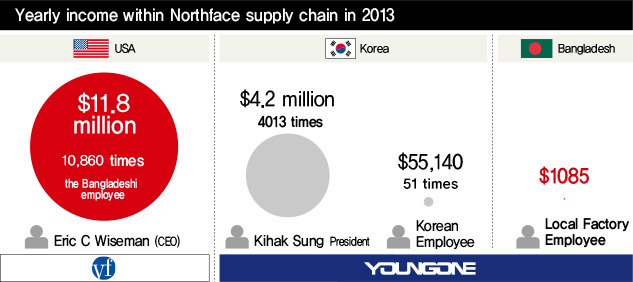

Sung’s reported earnings last year are equivalent to what 4,000 Bangladeshi Youngone workers earn in a year.

Stockholders of the two listed companies of Youngone in South Korea decided to pay total dividends of 15 billion won (US$14 million). For keeping stocks for a year, the stockholders altogether earn the equivalent of 12,000 Bangladeshi workers’ annual salaries.

60,000 Bangladeshi Youngone workers produce around 1 trillion won (US$945 million) worth of clothes and shoes per year. That‘s more than half of Youngone group’s total sales. Youngone recorded operating profits of 200 billion won (US$189 million) last year. Its operating profit to sales ratio was over 15%, which was higher than Samsung Electronics’ 13%. The uncelebrated company in a labor intensive industry is more profitable than the company that dominates global smartphone market.

Despite the minimum wage increase in Bangladesh, followed by the protest that killed Parvin and injured more than 10 workers, Youngone outperformed market expectations in the first quarter. Its sales increased 31%, operating profits 18%, over the same period the previous year. Yongones’ figures were not affected in 2010 when the clash was more serious.

Youngone spent 21.5 billion won (US$20.4 million) on advertising in South Korea last year - more than 18,000 Bangladeshi workers’ annual earnings. Most of that money is spent on TV commercials for Northface.

The owner of the brand Northface is in the United States. The company named VF headquartered in Greensboro, North Carolina owns Northface and about 20 more brands, including 7 For All Mankind, Reef, Nautica, Wrangler, Lee, Napapijri. Its sales are about 10 times bigger than Youngone. In 2013 it recorded US$10.9 billion in sales and operating profits $1.6 billion according to its own accounting report. VF CEO Eric C. Wiseman was paid $11.8 million. About 40% of the Northface products VF sells around the world are manufactured by Youngone.

Parvin was producing shoes for Puma. This German brand recorded sales of €2.98 billion (US$3.79 billion). Global brands such as Zara of Spain, H&M of Sweden, Uniqlo of Japan achieve 10-20 billion dollars of sales by sourcing from factories in the Third World.

Outdoor brands sell well in South Korea. They sell US$6.5 billion per year. Many South Koreans wear outdoor jackets, shirts and trousers as everyday wear. Most department stores in Seoul have a whole floor filled with outdoor brand stores. And Northface has been the highest selling outdoor brand in South Korea for many years.

A Northface shop in a department store in downtown Seoul. Northface has been the top selling outdoor brand in South Korea for many years. Almost every year consumer groups criticize Northface for its high prices, but they don’t pay attention to the Bangladeshi workers who make Northface products, earning less than $100 a month and lose their lives while asking for higher wages. (by Yoo Shin-jae, staff reporter)

A Northface shop manager in a department store in downtown Seoul welcomed us. He said he started his career as an employee of Youngone, but switched to running his own business several years ago.

Most fashion brands in South Korea do not operate stores with their own employees, but with self employed people often called ‘shop masters’. Shop masters employ clerks. Clerks are irrregular jobs. They are usually employed according to verbal contracts, and earn a little bit more than the minimum wage of 5,210 won (US$4.90) per hour. By outsourcing retail, fashion companies are minimizing direct employment costs.

When asked if customers care where the products are made, the Northface shop manager answered they do. “Yes, the customers are very sensitive about where the products are made”, he said. “They prefer ‘made in Korea’. If a product is from Bangladesh or Vietnam, many customers raise doubts about its quality.”

Not many South Korean customers are interested in what’s happening in Bangladesh, in the supply chain.

Youngone says this story is “unimaginable and not true”.

This digital story is a reproduction of the story which was originally printed on Hankyoreh Newspaper from August 25 to 29 in Korean.

Youngone does not deny that there were clashes in its factories in Bangladesh in December 2010 and January 2014. However Youngone has different views on the cause and victims of those clashes.

When asked whether the male workers of YSL had been assaulted after being called by managers on 11 December 2010, Youngone answered “It’s unimaginable and not true”. Youngone claimed “When we were in the process of applying the new minimum wage scale, unidentified men from outside raided seven of our factories simultaneously, and they broke into YSL factory which was adjacent to the street”. Youngone claimed none of its workers were harmed, but its managers were severely injured and $22,000 worth of damage was done to the company.

Youngone denied any correlation with the clash that occurred in front of CEPZ on the next day. Youngone said “The protest was not about problem in our factory. It was not about Youngone alone. It was the result of outside forces aggravating workers’ discontent at the new minimum wage scale.”

Youngone has similar explanation for Parvin’s death in last January. It said “Gross payment increased sharply due to the new minimum wage, but some workers had misunderstanding about the new wage scale”. It also added “Thugs from neighboring village broke into the factory, destroying facilities and stealing 7000 pairs of shoes which were waiting to be exported”.

We gave Youngone opportunity to be heard, and its claims were quoted in the story printed in August. Nevertheless, Youngone claimed it had been libeled by the story, and filed a petition to the Korean Press Arbitration Commission. The hearing was held on 29 October, but the dispute was not settled by arbitration. Youngone asserted correction of news, but the commissioners overruled.

Youngone filed a lawsuit against Hankyoreh demanding correction of news and compensation of 300 million won($270,000) for libel on 21 November 2014.

Reported and written by Ryu Yi-geun, Yoo Shin-jae Photo by Lee Jeong-a, Kim Myung-jin

Video editor Jung Ju-yong Digital producer Cho Sung-hyon

COPYRIGHT ⓒ2014 HANKYOREH. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

How pay raise killed workers: The story of a North Face manufacturer in Bangladesh

A news brief from Bangladesh reached Seoul last January. A female worker was shot dead by police in a factory owned by Youngone, the Korean sportswear manufacturer known as the biggest supplier of The Northface and the biggest foreign investor in Bangladesh. Youngone issued a short press release in Seoul through a PR firm.

scroll down ⊻

“There was a misunderstanding among some of the workers in the process of applying the new minimum wage scale, which led to unrest. Police opened fire, killing 1 worker and injuring 10 others. Meanwhile thugs from neighboring village broke into the factory, destroying facilities and stealing 2000-3000 pairs of shoes which were waiting to be exported. The management will repair the damage and clean the factory on Jan 11, and is endeavoring to resume operation on Jan 12. We feel sorry about this unfortunate incident, and ask for your understanding and cooperation.”